Originally published January 19, 2002 in The News (Mexico City)

Originally published January 19, 2002 in The News (Mexico City)Intricate art connects Huichol with their spiritual beliefs

Throughout Mexico, vestiges of an uneasy balance between pre-Hispanic cultures and the Spanish conquest linger. Scenes of cathedrals built on top of ancient temples, for example, demonstrate a country born of both worlds.

In Guadalajara, famously advertised as the most Mexican of cities – birthplace of mariachis, centre of the tequila industry – evidence of indigenous cultures is no t readily seen behind the colonial and neoclassical architecture and the proudly mestizo people.

However, in the suburb of Zapopan, next to the Basilica, a museum honours the traditions of the Huichol tribe of Jalisco and Nayarit – one intriguing example of the juxtaposition, rather than blending, of Catholicism with indigenous beliefs.

Begun in 1961 by Father Ernesto Loera, who wanted to raise funds for his mission among the Huichol as well as to preserve their heritage, the museum offers a glimpse into a culture which, thanks to its relative isolation in the Sierra Madre, has been largely inaccessible to tourists and the encroaching world. The Huichol, according to ethnologist Peter Furst, “represent the only Mesoamerican population whose aboriginal ideological universe has remained basically unaltered by Christian influence.”

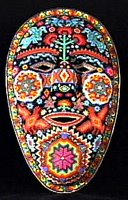

These beliefs are spelled out in the museum's displays, which cover both everyday life, including houses, clothing and government, and spiritual beliefs, illustrated with the yarn designs and beadwork that have become the Huichol's artistic trademark.

Yarn artworks, a relatively recent production, have their roots in God's eyes, small offerings made of yarn which serve as a window into the spiritual world for the Huichol. Today's larger, more elaborate yarn designs are produced for sale – one hint that the Huichol way of life can hardly be considered untouched by the outside world. Still, they retain images of important symbols,such as deer and corn, two of the most important natural elements defined in the Huichol mythology.

“Through their artwork, the Huichol encode and document their spiritual knowledge,” noted Susana Eger Valadez in her book Huichol Indian Sacred Art. “From the time they are children, the Huichol learn to communicate with the spirit world through symbols and rituals. Thus for the Huichol, yarn painting is much more than mere aesthetic expression.”

For example, one yarn work in the shape of the sun, illustrated with animal and plant images, celebrates one of the most important forces in the Huichol world. “In the indigenous world, the sun gives us the greatest gifts and illuminates the path of the shaman,” explained the artist, Julio Carrillo Acosta. “when the shaman reaches the highest level of shamanism, he comes into contact with all creatures.”

The hallucinogenic cactus peyote plays a central role in the Huichol quest for enlightenment and shamanic power, as well as in their art. Every spring, a group of Huichol make a pilgrimage to the hills around Real de Catorce to collect peyote and partake in rituals at this sacred place, which they know as Wirikuta.

Many of the yarn artists begin their creations with no previous pattern, allowing their fingers to follow their imaginations and their memories of peyote-induced visions. Several of their colourful creations are on display in the museum, and the gift shop contains many small and large pieces for sale, along with beaded sculptures and other crafts.

The museum signage is translated into poor English, sometimes with unfortunate results. For example, the term “Maarakame,” referring to Huichol shamen, is rendered as “quack doctor.” Still, the explanations for the Huichol world view are worth wading through for the insight they offer into the beliefs of a living culture not readily available to the average sightseer.

The Huichol Museum is located at the Basilica of Zapopan, Plaza de las Americas, corner of Hidalgo and Pino Suarez. Guadalajara city buses to Zapopan can be caught along 16 de Septiembre heading north.